Route d' Fromage

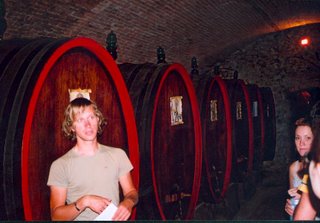

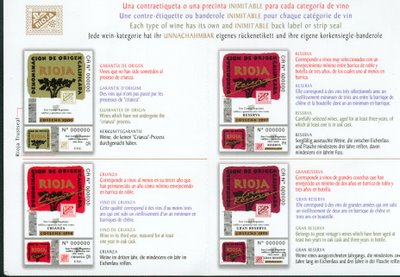

May 1st I arrived in Grenoble, France to meet up with my friend Yvonne who has a large extended family there. She had been cooking in Italy for the past six months and I had come to Europe six weeks early for my brother's wedding in Estonia (that's another story--see his blog Letters from Estonia). Our roughly sketched plan was to rent a car for a month; drive to Spain and hang out in Barcelona, La Rioja, and San Sebastian for a couple of weeks; head up to Pays Basque in France for a week or so of cheese adventures; on to Bordeaux, to visit Jean D'alos--master affineur--and to drink wine; and then back to Grenoble. Along the way we would try to hit a couple of Michelin starred restaurants and maybe stay at a few farm/bed & breakfast places. It was a pretty good plan--I speak passable Spanish (well, except on the phone) and Yvonne is almost fluent in French--and we shared the same roughly defined goals (eating and drinking well, visiting the source of the food, and laying in the sun) and degree of flexibility.

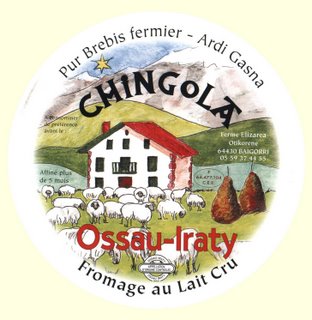

I became familiar with Basque sheep cheese from working for a few years at a cheese shop in San Francisco, Cowgirl Creamery, and from seeing it in the kitchens where I had worked as a cook. Of all the dozens of cheeses I came to know and love in my cheesemonger days I concluded that Basque sheep cheese was my favorite, specifically a few types that fall under the classification of Ossau-Iraty. While I have spent the past four years in the kitchen as a chef my true calling has always been farming, and for quite some time I've harbored the dream of raising sheep and making a Basque-style cheese. What follows is a summary of the basic information about Ossau-Iraty cheese I have gleaned over time.

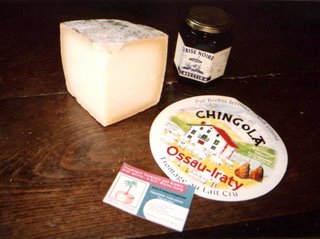

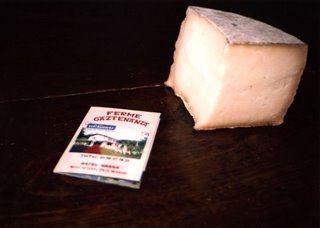

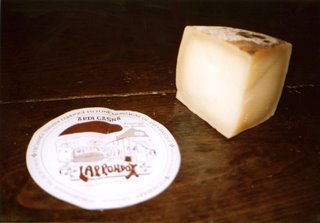

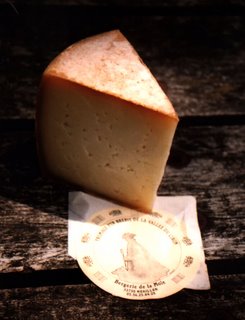

Ossau-Iraty is an Appellation d'Origine Controlee aged sheep cheese (not "cheap cheese") made in the Southwest of France in the Basque and Bearn regions. Ossau-Iraty is an aged cheese generally sold after about 3 or 4 months in wheels of around 2 kilos (~5 lbs). It has a smooth, creamy ivory-colored pate with small holes; a natural rind varying from orangish tan to black, white and grey mottled; and a buttery, nutty, slightly tangy fruit flavor. From what we could gather from the farms we visited, they do not add a culture to the milk in the cheesemaking process, only rennet. All of the cheesemakers we asked used chymosin, not natural rennet. The milk comes from a local race of Basco-bearnaise sheep, either red-headed Manech (Manex) or black-headed Manech.

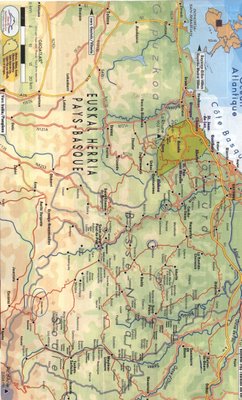

The sheep are usually milked from November or December to about May or June and then taken to graze in the mountain pastures during the summer. The area where Ossau-Iraty is produced is demarcated by the Ossau valley in the Bearn region on the east, the Pyrenees on the south, the Iraty forest in the Basque region to the west, and as far as I can tell the northern boundary is somewhere around the rivers of Adour and Gave de Pau. The D918 highway which runs from St. Jean de Luz on the Atlantic coast to close to the city of Pau is the Route de Fromage for Ossau-Iraty, lined with small farmstead cheesemakers that sell their products to the public.

The sheep are usually milked from November or December to about May or June and then taken to graze in the mountain pastures during the summer. The area where Ossau-Iraty is produced is demarcated by the Ossau valley in the Bearn region on the east, the Pyrenees on the south, the Iraty forest in the Basque region to the west, and as far as I can tell the northern boundary is somewhere around the rivers of Adour and Gave de Pau. The D918 highway which runs from St. Jean de Luz on the Atlantic coast to close to the city of Pau is the Route de Fromage for Ossau-Iraty, lined with small farmstead cheesemakers that sell their products to the public.

I did my best to plan our cheese visits in advance through a cheese contact in Spain, contact information for a couple of Ossau-Iraty makers that I got from the web, and the tentative connection I had with an affineur in Bordeaux. We had hoped to visit a benedictine monestary that makes a fantastic cheese called Abbaye d'Bellocq but we discovered that only people on religious journeys (accompanied by men) were allowed to visit and that they had contracted out the manufacture of the cheese some time ago. So much for my visions of hanging out with cossack clad monks as they stirred the curd by hand in aged wooden vats, chanting all the while. Anyway, I've traveled enough in the past to realize that winging it is usually more successful than trying to make advance arrangements from afar with people in relatively isolated locations, and this proved to be the case. My contact in Spain was able to connect us with a fairly large (by Spanish standards, not by US) cheese factory that produced Idiazabal--a Basque sheep cheese made in the Northwest of Spain that is similar to Ossau-Iraty but usually smoked. Yvonne also had a Routard guidebook to the farmstead producers of agricultural products and chambres d'hotes (B&Bs) of France who opened their doors to the public. This was an excellent resource, even though we actually only visited a few farms listed in the guide, because it led us to the right areas and roads to find farms on our own.

Yvonne and I spent the better part of a week driving the small windy roads of Pays Basque in search of sheep cheese. We quickly learned a few lessons: #1 Nothing is open and no one is available between the hours of 12noon and about 3 pm.

#2 A single map displaying all of the highways by name and all of the towns in the area does not exist, only an assortment of maps, each with partial information. Don't even bother trying to use a @#*&ing GPS system. #3 All roadsigns in Basque country have been systematically vandalized to obscure any French names of towns or places, leaving only the Basque names. #4 Basque people are extremely friendly and welcoming, with a rather wry sense of humor. #5 Almost all farms have really cool, friendly (yet filthy) dogs which you can't help but pet, invariably resulting in stinky dog hands. #6 A car full of ripe sheep cheese emits a rather pungent odor when left in the sun for any amount of time.

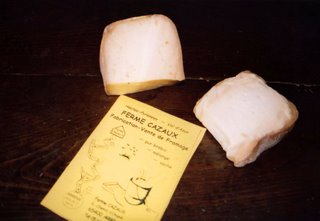

#2 A single map displaying all of the highways by name and all of the towns in the area does not exist, only an assortment of maps, each with partial information. Don't even bother trying to use a @#*&ing GPS system. #3 All roadsigns in Basque country have been systematically vandalized to obscure any French names of towns or places, leaving only the Basque names. #4 Basque people are extremely friendly and welcoming, with a rather wry sense of humor. #5 Almost all farms have really cool, friendly (yet filthy) dogs which you can't help but pet, invariably resulting in stinky dog hands. #6 A car full of ripe sheep cheese emits a rather pungent odor when left in the sun for any amount of time.Through the previously mentioned resources available to us at the beginning of our trip we were able to locate and contact a couple of known Ossau-Iraty makers and attempt visits. I don't think we actually successfully visited any of these farms but we were able to discover many other cheesemakers in the process. The first farm that we tried to visit, not once but twice, was Ferme (that's french for "farm") Antxondoa in a town called Itxassou. We missed the hours of operation for their little farmstand on both occasions, and furthermore they were finished making cheese for the season, having dried off the sheep to coincide with the harvest of their black cherry orchard. They were quite helpful, though, in directing us toward a relative's farm in St. Martin d'Aberoue. This second farm, Ferme Agerria, turned out to be an excellent place to begin our cheese exploration as they have made a significant effort to be visiter-friendly and informative, even filming a video about the cheesemaking process with narration in Basque, French, Spanish and English (although they had only completed the Basque version at the time of our visit). In addition, we collected a couple new brochures and maps of the region listing other Ossau-Iraty makers.

Our visits to cheesemakers generally followed one of two patterns. In the first scenario we would arrive at a rather quiet little farm and wander around for a few minutes, making friends with the scroungy farm dogs, until being greeted by a little old lady in a housecoat or a little old man in a beret who would sell us a piece of cheese. For the other visits the actual cheesemaker was on hand, in a few cases in the middle of making cheese, and we were able to get a little tour of the facility and ask a barrange of questions. Well, I would ask questions in English, Yvonne would translate into French, they would answer her in French while I tried to pick out recognizable words and then she would translate the answers again for me. After 2 or 3 farms the process got a little more streamlined as Yvonne already knew the questions I wanted to ask and I had a better guess at what the answers would be. Although I was the source of most of the questions I found that with one exception the cheesemakers would all speak directly to Yvonne and ignore me.

[The exception was a relatively young single Basque guy who seemed rather keen to communicate with me, which led to a degree of girlish giggling and Yvonne's insistance on calling him my boyfriend. He ran the farm with his brother and we did briefly consider the possibility of marrying the two brothers and becoming Basque farmwives, but we got stuck on the issue of who would get the better looking one (with hopes that it was the unseen brother).]

Without fail we would conclude each farm visit by purchasing a whole wheel or a large chunk of cheese and some local cherry jam, dried prunes, cider or what have you.

Visiting roughly ten farms meant that by the end of the week we had purchased about ten kilos (over 20 lbs) of sheep cheese, not including the four small wheels of Idiazabal cheese we had brought with us from Spain! Our almost daily lunch became a picnic of fresh bread, some type of salami or cured meat, an assortment of cheeses, cherry jam, prunes, pistachios and occassionally wine from our stash bought in La Rioja. Our digestive systems insisted upon the occasional break from this routine and we vowed to go on all fruit fasts when we returned to Grenoble. Our picnics did provide an opportunity to compare and contrast the surprisingly significant variations in flavor and texture among our cheese samples. In order to keep track of the origins of each piece we found ourselves resorting to an offhand system of nicknames for each of the farms and cheesemakers. "Old fly man", "cheeky Basque guy", "housecoat lady with bare-necked chickens", "rosy-cheeked fly lady", and "flirty bachelor guy" proved much more memorable labels than the actual farm names.

Visiting roughly ten farms meant that by the end of the week we had purchased about ten kilos (over 20 lbs) of sheep cheese, not including the four small wheels of Idiazabal cheese we had brought with us from Spain! Our almost daily lunch became a picnic of fresh bread, some type of salami or cured meat, an assortment of cheeses, cherry jam, prunes, pistachios and occassionally wine from our stash bought in La Rioja. Our digestive systems insisted upon the occasional break from this routine and we vowed to go on all fruit fasts when we returned to Grenoble. Our picnics did provide an opportunity to compare and contrast the surprisingly significant variations in flavor and texture among our cheese samples. In order to keep track of the origins of each piece we found ourselves resorting to an offhand system of nicknames for each of the farms and cheesemakers. "Old fly man", "cheeky Basque guy", "housecoat lady with bare-necked chickens", "rosy-cheeked fly lady", and "flirty bachelor guy" proved much more memorable labels than the actual farm names.